- Home

- Judith Newman

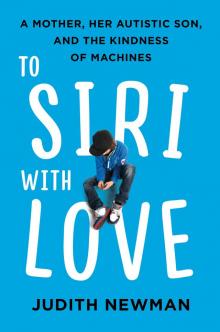

To Siri with Love

To Siri with Love Read online

Epigraph

For as he thinketh in his heart, so is he.

—Proverbs 23:7

“Look, Mommy, that bus says, ‘Make a Wish.’ What’s your wish?”

“My wish is for your happiness, health, and safety your whole life, Gus. What’s your wish?”

“My wish is to live in New York City my whole life, and to be a really friendly guy.”

“But not too friendly, right?”

“What’s ‘too friendly’?”

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Epigraph

Author’s Note

Introduction

One: Oh No

Two: Why?

Three: Again Again Again

Four: I, Tunes

Five: Vroom

Six: Blush

Seven: Go

Eight: Doc

Nine: Snore

Ten: To Siri with Love

Eleven: Work It

Twelve: Chums

Thirteen: Getting Some

Fourteen: Toast

Fifteen: Bye

Acknowledgments

Resource List

About the Author

Also by Judith Newman

Copyright

About the Publisher

Author’s Note

These days, it’s considered politically incorrect to call a person “autistic.” If you do, you are defining that person entirely by his or her disability. Instead, you’re supposed to use “person-first” language: a man with autism, a woman with autism.

I understand the thinking here. It’s like calling a person who has dwarfism a dwarf; is short stature the one thing that defines him or her as a human being? But as a tiny friend said to me recently, “Oh, for God’s sakes, just call me a dwarf. It’s the first thing you see, and I know it’s not the only thing about me that’s interesting.”

“Person with autism” also suggests that autism is something bad that one needs distance from. You’d never say “a person with left-handedness” or “a person with Jewishness.” Then again, you might say “a person with cancer.”

Autism does not entirely define my son, but it informs so much about him and our life together. Saying autism is something you are “with” suggests it’s something you carry around and can drop at will, like a purse. There’s also something about this pseudo delicacy that is patronizing as hell. Not that I’m against every carefully considered word for disability. I just want the words to be true. When you call autistic people “neurodivergent,” for example, you are not stretching for political correctness; you are accurately describing their condition.

(I am all for finding new language that is descriptive and fun and to the point. If you want to ask delicately if someone is autistic, how about asking if he or she is a FOT—Friend of Trains? I mean, if there can be Friends of Dorothy . . . )

There’s yet another reason I use the term “autistic” freely here: you try writing an entire book using the phrase “person with autism” over and over again. It’s clunky. So I will sometimes refer to men and women here as autistic. I will also defer to the masculine pronoun when I am talking about people in generalities, because I learned that it was correct to do this sometime back when dinosaurs roamed the earth. I mention this because a friend just wrote an excellent book on parenting using the pronoun “they” instead of “he or she,” and she uses the term “cisgender” to refer to anyone who is well, cisgender, which is one of the at least fifty-eight gender options offered by Facebook, ranging from Agender to TwoSpirit. She did this at the insistence of her teenage daughter. Language needs to evolve, but not into something ugly and imprecise. I read her book simultaneously loving her parenting philosophy and wanting to punch her in the face.

But whatever her crimes against the English language, my friend consulted with her kids about their place in her book. I did not. This is both selfish and necessary. While Gus’s good-natured attitude about being my subject has always been, “I will be a celebrity, Mommy,” Henry’s feelings change with his mood. At first, he was cavalier in a way guaranteed to irritate me: “Oh, it doesn’t matter, I never read what you write anyway.” At that point there was talk about whether he would get a share of the profits, and a quick glance at his computer’s Google history revealed the phrase “film option.” Then, when it dawned on him that people he knows actually do read, he panicked a little. So writing about him became a negotiation, which sometimes he won and sometimes he lost. He was fine about being portrayed as a smart-ass bro. What he worried about was that I might reveal him to be the sweet, caring, wonderful soon-to-be man he really is. I only slipped a little.

There are many good, some great, books about autism (see Resources, page TK)—about the science, the history, treatments. While this book touches on all these subjects, you will never see a review of it that begins, “If you have to read one book about autism . . .” This is not that One Book. It is a slice of life for one family, one kid. But I hope it seems sort of a slice of your life, too.

When I wrote the original story about Gus and Siri for the New York Times, Gus was twelve. Most of this book takes place when my sons are thirteen and fourteen. When the publisher tears the manuscript from my hands, they will be fifteen, then sixteen when it hits the remainder bin. Kids grow older, and I wanted this book to be accurate, so I would still be writing and changing it if my agent hadn’t called me one day and said, “For the love of God, just put a period on it.”

So I did.

Introduction

My kids and I are at the supermarket.

“We need turkey and ham!”

Gus tends to speak in exclamation points. “A half pound! And . . . what, Mommy?” I’m stage-whispering directions, trying to keep the conversation focused on deli meats. Behind the counter, Otto politely slices and listens, occasionally interjecting questions. We’re on track here.

And then . . . we’re not.

“So! My daddy has been in London for ten days, and he comes back in four days, on Wednesday. He comes in to JFK Airport on American Airlines Flight 100, at Terminal Eight,” Gus says, warming to the subject. “What? Yes, Mom says thin slices. Also, coleslaw! Daddy will take the A train from Howard Beach to West 4th and then change to the B or D to Broadway–Lafayette. He’ll arrive at 77 Bleecker in the morning and then he and Mommy will do sex . . .”

Suddenly Otto is interested. “What?”

“You know, my daddy? The one who is old and has bad knees? He arrives at Terminal Eight at Kennedy Airport. But first he has to leave from London at King’s Cross, which goes to Heathrow, and the plane from Heathrow leaves out of—”

“No, Gus, the other part,” says Otto, smiling. “What does Daddy do when he gets home?”

Gus presses on with his explanation, ignoring the little detail his twin brother, Henry, whispered in his ear. Henry stands off to the side, smirking, while Gus continues with what really interests him: the stops on the A line from Howard Beach. I see the slightly alarmed looks on the faces of the people waiting in line. Is it the content of Gus’s chatter or the fact that he is hopping up and down while he delivers it? When he’s happy and excited, which is much of the time, he hops. I’m so used to it I barely notice. But in that moment I see our family the way the rest of the world sees us: the obnoxious teenager, pretending he doesn’t know us; the crazy jumping bean, nattering on about the A train; the frazzled, fanny-pack-sporting mother, now part of an unappetizing visual of two ancients on a booty call.

Yet I want to turn to everyone in line and say, “You should all be congratulating us. Several years ago, Hoppy over there would hardly have been talking at all, and whatever he said would have been incomprehensible. Sure, we have a few glitc

hes to work out. But you’re missing the point. My son is ordering ham. Score!”

You may recognize Gus as my autistic son who recently enjoyed his fifteen minutes of fame. I wrote a story for the New York Times called “To Siri, With Love,” about his friendship with Siri, Apple’s “intelligent personal assistant.” It was a simple piece about how this amiable robot provides so much to my communication-impaired kid: not just information on arcane, sleep-inducing subjects (if you’re not a herpetologist, I’m guessing you’re about as eager as I am to talk about red-eared slider turtles) but also lessons in etiquette, listening, and what most of us take for granted, the nuances of back-and-forth dialogue. The subject is close to my heart—it’s my son, so how could it not be?—but I thought the audience for this sort of thing was limited. Maybe I’d get a few pats on the back from friends.

Instead, the story went viral. It was the most-viewed, most-emailed, most-tweeted NYT piece for a solid week. There were magazine, television, and radio pieces around the world. There were letters like this:

You may be aware that right now a huge effort is being made by Apple to make Siri available in other languages. I am Russian translator for Siri, and I can say that sometimes it is very hard to transfer Siri personality to another culture. You really helped me a lot to understand, how Siri should behavior in my language, with so great examples of what people are really expecting from Siri to say. And your thesis about kindness of machine towards people with disabilities just had made me cry. We had a talk about your article in our team, and it was very beneficial for general translation efforts for Siri.

So, with your help, Russian Siri would be even more kind and friendly, and supporting. I always keep in mind your son Gus, when writing the dialogs for Siri in Russian.

This letter moved me deeply, as did the hundreds of emails and tweets and comments from both parents of children with autism and autistic people themselves (not that they always identified themselves as such, but when a guy tweets different lines from your piece over and over and over, you can figure it out). I think my favorite letter was from a man who wrote to the editor: “This author has a future as a writer.”

Why did this story hit a nerve? Well, for one thing, it presented an opposing view to the current notion that technology dumbs us down and is as bad for us as Cheetos. But its popularity also, I believe, stems from its being about finding solace and companionship in an unexpected place. As we disappear into our phones, tablets, smart watches, and the next smart thing, it’s all too tempting to disengage. These days, it’s easy for everyone to feel a little lonely.

But here was a counter point of view. Technology can also bring us out a little and reinforce social behavior. It can be a bridge, not a wall.

I realized there was a great deal more to say about the “average” autistic kid. Narratives of autism tend to be about the extremes. Behold the eccentric genius who will one day be running NASA! (Well, someone has to get a human to another galaxy; you didn’t think it would be someone neurotypical, did you?) And here is the person so impaired, he is smashing his head against the wall and finger painting with the blood. What about the vast number of people in between?

That’s my son Gus.

* * *

No two people with autism are the same; its precise form or expression is different in every case. Moreover, there may be a most intricate (and potentially creative) interaction between the autistic traits and the other qualities of the individual. So, while a single glance may suffice for clinical diagnosis, if we hope to understand the autistic individual, nothing less than a total biography will do.

—Oliver Sacks, An Anthropologist on Mars, 1995

The most recent stats for an autism diagnosis are startling. In the 1980s, about one in two thousand American kids was diagnosed with autism. Today the number is around one in sixty-eight, according to estimates from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network. Among boys, it’s one out of forty-two. In some countries the numbers are lower; in some, higher (South Korea claims about 2.6 percent of their population has autism, as compared to our 1.6). It is the fastest growing developmental disability in the world, affecting 1 percent of all people. A University of California, Davis, study published in 2015 in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders found that the total cost for caring for people with autism in the United States in 2015 was $268 billion, and this number is forecasted to rise to $461 billion by 2025. This represents more than double the combined costs of stroke and hypertension.

How is that possible? Researchers and writers want to know what the hell is happening. Whether its increasing prevalence is because of something toxic in the water/air/ground, whether it’s because people who were once diagnosed with other mental conditions are now labeled autistic, or whether it’s because slightly odd people who used to be single are having more of a chance to breed, thereby creating even odder people (the Silicon Valley hypothesis), no one is certain. It might be a combination of all three.

Related conditions once categorized as autism, including Asperger’s syndrome and pervasive developmental disorder, are now referred to under the umbrella of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). That’s because the disabilities—and abilities—exist on a spectrum. Verbal or nonverbal, cognitively impaired or cognitively off-the-charts brilliant—these often very scattered abilities can exist in a confounding stew. Moreover, people with ASD don’t develop skills in the kind of steady progression of neurotypical children; there’s more of a herky-jerky quality to mental and emotional growth, meaning that they may not be able to do something for a very long time and then, one day, they just can.

My favorite story of this phenomenon involves a friend whose son didn’t talk at all, save for a word here and there when he needed something. “Cookie.” “Juice.” He was five. One day on his way home from a party, some kids following him were mocking him in a sing-song voice about being unable to speak: “Luke can’t talk, Luke can’t talk.” After a few minutes he turned around and said, “Yes, I can. Go fuck yourselves.”

I also love hearing stories about brilliant people in history who are now thought to be autistic, not because I think my own son is going to suddenly reveal himself to be some sort of genius, but because it’s a reminder that the progress of human civilization flourishes with profound oddity and an ability to fixate on a problem. Albert Einstein used to have trouble speaking as a child, repeating sentences like an automaton instead of conversing. Isaac Newton rarely spoke, had few friends, and stuck with routines whether or not they made any sense. If, for example, he was scheduled to give a speech, it’s said he’d give it whether there was anyone there to listen or not. Thomas Jefferson, according to Alexander Hamilton, couldn’t make eye contact with people and couldn’t stand loud noises. While he was a beautiful writer, he avoided communication with people verbally. The artists Andy Warhol and Michelangelo, the actor Dan Aykroyd, the director Tim Burton . . . the list goes on and on.

The phrase “When you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism” is a favorite in the ASD community. But there are three common denominators I can think of. One, every person with ASD I’ve ever met has some deficit in his “theory of mind.” Theory of mind is the ability to understand, first, that we have wishes and desires and a way of looking at the world—i.e., self-awareness. But then, on top of that, it’s knowing that other people have wishes and desires and a worldview that differs from yours. It is very hard, and sometimes impossible, for a person with autism to infer what someone else means or what he or she will do.

Several brain-imaging studies on autistic kids show a pronounced difference in blood flow in the areas of the brain that are thought to be responsible for certain kinds of story comprehension—the kind that allows us to know what the characters are feeling, and predict what they might do next. I thought about this recently when I was at an event for my son’s special needs school, and this one guy—maybe e

ighteen, obviously smart and in some ways sophisticated—came over and hugged me. Then, a few minutes later, he hugged me again. Hugging! It felt good. Why wouldn’t I enjoy it, too? Someone pulled him aside and told him that maybe five times was enough with a stranger. He nodded, waited till she was gone . . . and hugged me again.

Second, every person with ASD I’ve ever met loves repetition and detail in some form or another; if a subject is interesting to him, there is no such thing as “getting tired” of it. This can make people delightful or exhausting companions, depending how much you want to hear about, say, wind shears and suction vortices. (People with ASD are well represented in the meteorology community, I’m told. Also on Wikipedia. If you want to know who’s constantly monitoring and updating pages on things like public transport timetables and the list of guest stars on Sesame Street, look no further than the ASD community.)

And the third? Objectively they are all a little out there. If Gus had been born in the early to mid-twentieth century, the pressure to institutionalize him would have been enormous. Even Dr. Spock, the man who famously told mothers in 1946, “You know more than you think you do,” and urged them to follow their instincts, recommended they institutionalize “defective” children. (“It is usually recommended that this be done right after birth,” he wrote. “Then the parents will not become too wrapped up in a child who will not develop very far.”) And it’s not as if the idea of a “final solution” to autism is a historical curiosity. A few years ago, in the Netherlands, where euthanasia is legal not only for incurable physical conditions but also for mental conditions thought incurable and unbearable, an autistic man who had all his life been unable to form friendships asked to be put to death. His wish was granted.

But the fact is: they are here, they are weird, get used to it. Neurologically divergent people are your neighbors, work colleagues, and, perhaps, your friends and family.

To Siri with Love

To Siri with Love